An essay by

Gary M. Lavergne

After

deciding to write about the darkest day in Austin’s history, August 1,

1966, I approached the Charles Whitman story as others who had written

it. I searched for the "demon" that possessed him. In the process,

I learned a great deal about many things, including much about the burdens

of writing history.

After

deciding to write about the darkest day in Austin’s history, August 1,

1966, I approached the Charles Whitman story as others who had written

it. I searched for the "demon" that possessed him. In the process,

I learned a great deal about many things, including much about the burdens

of writing history.

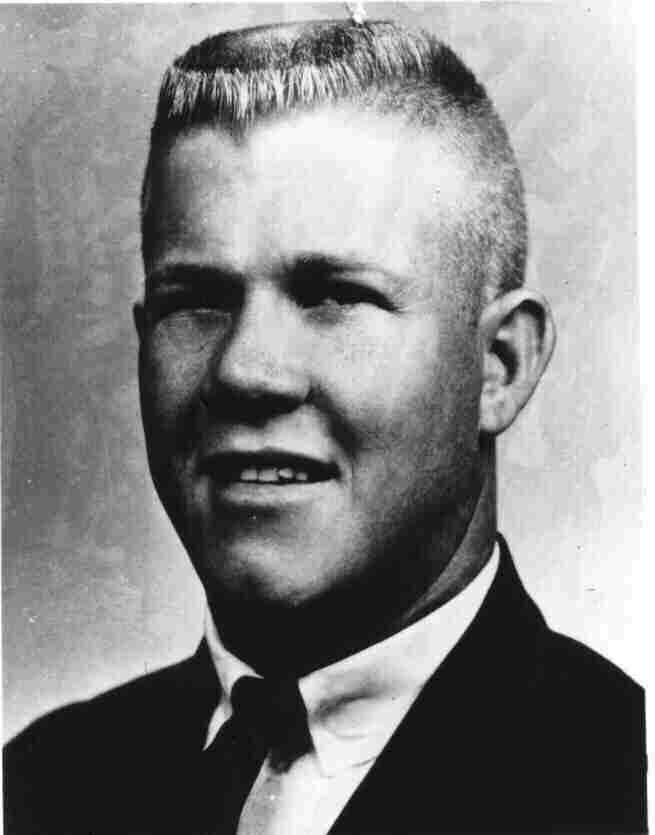

Many Austinites still passionately remember August 1, 1966, as the day a sleepy college town lost its innocence. Over the next 30 years a great deal would be written about the handsome, blonde crew-cut ex-marine who was directly responsible for the slaughter that caused so much pain. Much of the writing would be accurate and insightful, but just as much of it amounted to disinformation generated by the twin enemies of history -- passion and folklore.

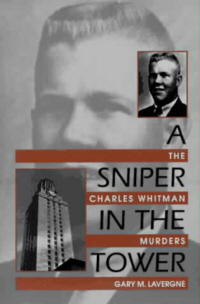

Those

familiar with the story know many theories have been postulated as "causes"

for his murderous rampage. Those causes still plague America today in the

form of emotional debates. Domestic violence, child abuse, drug abuse,

violence against women, gun control, violence depicted by the mass media,

the breakdown of the family, and organic causes of violence were all issues

I had to study to produce A

Sniper in the Tower. Each evokes strong reactions from powerful

advocacy groups, and rightly so; they are the issues of our time.

Those

familiar with the story know many theories have been postulated as "causes"

for his murderous rampage. Those causes still plague America today in the

form of emotional debates. Domestic violence, child abuse, drug abuse,

violence against women, gun control, violence depicted by the mass media,

the breakdown of the family, and organic causes of violence were all issues

I had to study to produce A

Sniper in the Tower. Each evokes strong reactions from powerful

advocacy groups, and rightly so; they are the issues of our time.

I have very strong opinions on all of the issues mentioned above, as do most Americans. Often, I found myself wanting to use Charles Whitman to express my outrage, but it is the burden of writing history to view events in a balanced and dispassionate manner. Readers should feel passion when reading history; writers cannot afford that luxury when writing it. Purging passion from history takes courage. For example, Gerald Posner, the author of Case Closed, showed courage in producing a brilliant defense of the Warren Commission conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he killed JFK. He did so at a time when more than 70 percent of Americans believe in dozens of different conspiracies as passionately as they loved and respected JFK.

The one time I doubted the wisdom of my decision

to write about the University of Texas Tower tragedy was during a visit

to a most graceful and dignified retired neurosurgeon named Dr. Albert

Lalonde. My heart sank when he respectfully yet directly asked, "So

why do you want to dredge this up again?" His question and my very

clumsy answer still haunt me. I wish I had found the presence  of

mind to answer that it is the burden of writing history to clarify or prevent

folklore, especially in regards to evil. A dispassionate look at Charles

Whitman exposes a folklore which bestows on him a profile he does not deserve.

Without history, folklore creates legends out of criminals. Consider Jesse

James, Billy the Kid, Bonnie and Clyde, and closer to home, Sam Bass and

Wild Bill Longley. Myths have supplanted the truth about their evil ways.

All have streets, buildings, stores, movies, and even festivals named after

them, and their graves are significant tourist attractions. Nearly all

of them

of

mind to answer that it is the burden of writing history to clarify or prevent

folklore, especially in regards to evil. A dispassionate look at Charles

Whitman exposes a folklore which bestows on him a profile he does not deserve.

Without history, folklore creates legends out of criminals. Consider Jesse

James, Billy the Kid, Bonnie and Clyde, and closer to home, Sam Bass and

Wild Bill Longley. Myths have supplanted the truth about their evil ways.

All have streets, buildings, stores, movies, and even festivals named after

them, and their graves are significant tourist attractions. Nearly all

of them have

had impostors claiming to be "the real thing." Some, like Jesse

James and Bill Longley, have been exhumed for DNA testing to settle bitter

feuds between "rightful heirs" to a romantic legacy. All are

examples of the failure or neglect of historians. For example, while visiting

the "Billy the Kid Gift Shop" in New Mexico, my son Mark gazed

at a poster of The Kid and observed that "he was pretty ugly."

The cashier countered that the Kid was actually quite handsome and that

"he had a way with the girls." We all have folklore we cherish;

replacing it with history takes courage. Such is the burden of writing

history.

Today, Austinites are rightly affronted at the idea of naming a street after Charles Whitman, but the elements of a Charles Whitman legend are already in place. Many consider him to have been nice, mature, hard-working, and handsome. He has been characterized as an honor student, an all-American boy, a good son, loving husband and model marine. Today, vendors sell T-shirts depicting the UT Tower, Whitman, and the slogan "support your school." Many good people have passionately portrayed him as the victim of a cause they champion, and in this story there are many causes from which to choose. After trying to do justice to all of the views, I could only decide on the painfully obvious: that Charles Whitman made an evil decision to become a murderer. I never wanted to believe it. In a way, it scared me; but such is the burden of writing history.

The gulf between the folklore and the facts about Charles Whitman is large, indeed. The victims of his violence, along with those who risked their lives to rescue the wounded, deserve the unveiling of the man who would have killed even more people if given the chance. History must insure that those gunned down will be remembered as having been attacked by a murderer, not a legend. It would have been easier to claim to "discover" a cause for what Whitman did, to attach it to something everyone loathes, like drugs, child abuse, or domestic violence, or simply to say that anyone who would commit such a crime had to be crazy. I could not; that is passion which contributes to legend, not history. And such is the burden of writing history.

| Gary's Bio |Before Brown| Worse Than Death| Bad Boy From Rosebud | Sniper in the Tower | Cajuns |