PROLOGUE

WEATHERED METAL PLAQUES

U.S. Highway 59 in Texas spans both rural and urban areas. Through Houston the traffic can be murderous, but just south of the metro area, near Rosenberg, drivers breathe a sigh of relief. They are safely into the countryside. Rosenberg inhabitants, like many small-town Texans, worry about how "planned communities" of deed-restricted, monotonous, brick homes creep closer. They cling to an agrarian tradition while welcoming vast riches from the oil and gas industry. Crops of all types carpet tracts of rich, dark soil, while oil-searching and producing rigs dot the landscape.

Near the exit to FM 2218 are the Davis-Greenlawn Funeral Chapel and a large, well-manicured cemetery. Golf carts transport visitors and maintenance personnel. The main entrance is near the access road, but many visitors are attracted to a smaller, less ostentatious entrance on the northeast side. The bumpy path leads to an even smaller drive, where blades of grass struggle to grow through compacted gravel. At the confluence is a large white marble carving of Da Vinci's Last Supper. That portion of the cemetery is nearly full, and unoccupied sites have long ago been sold and await their inhabitants. The graves are marked by weathered metal plaques on small marble slabs. Visitors are seldom distracted by the traffic noise from Highway 59; more noticeable are the chirping birds in a nearby wooded area. Here is peace.

Kathleen Leissner Whitman is buried here. Gothic lettering on her

plaque indicates that she was born in 1943 and died in 1966. Far too young to have found the peace of a grave, she lies beneath an oak

tree. Nearby, weak and rotted limbs from a towering pine fall to the ground

as if to join the dead. The family service director of Davis-Greenlawn

Cemetery steps off a golf cart and volunteers, "Hardly anyone ever

comes here anymore, and few people around here even know who she is, but

many of the old timers tell me that reporters from all over the world were

here for her funeral." Attached to the weathered plaque is a small

black vase with nearly-fresh poinsettias. "I see to it that flowers

are there, at least most of the time. I kind of adopted her. It just seems

right."

Far too young to have found the peace of a grave, she lies beneath an oak

tree. Nearby, weak and rotted limbs from a towering pine fall to the ground

as if to join the dead. The family service director of Davis-Greenlawn

Cemetery steps off a golf cart and volunteers, "Hardly anyone ever

comes here anymore, and few people around here even know who she is, but

many of the old timers tell me that reporters from all over the world were

here for her funeral." Attached to the weathered plaque is a small

black vase with nearly-fresh poinsettias. "I see to it that flowers

are there, at least most of the time. I kind of adopted her. It just seems

right."

Knowing what

Kathy Whitman looked like makes the visit more tragic. She was beautiful.

Knowing that she chose teaching as an honorable profession brings pointless

questions of the lives she could have touched; the world was robbed of

her grace, intellect and talent. Knowing that on her last day she fell

asleep feeling safe and that her death came quickly and painlessly brings

little comfort. She has occupied space 5, lot 42 of section H of Davis-Greenlawn

Memorial Park since 3 August 1966.

Knowing what

Kathy Whitman looked like makes the visit more tragic. She was beautiful.

Knowing that she chose teaching as an honorable profession brings pointless

questions of the lives she could have touched; the world was robbed of

her grace, intellect and talent. Knowing that on her last day she fell

asleep feeling safe and that her death came quickly and painlessly brings

little comfort. She has occupied space 5, lot 42 of section H of Davis-Greenlawn

Memorial Park since 3 August 1966.

Approximately 1,200 miles away, via the Eisenhower Interstate System, in West Palm Beach, Florida, is Hillcrest Memorial Park. Across the street from a large, domed silver water storage tank, a life-size statue above a small columbarium depicts a mother and father looking down upon their young son and daughter with gentleness and kindness. At the base of the statue is inscribed "Family Protection." Here, too, is peace.

At Hillcrest narrow asphalt roads wind among the weathered metal plaques. Some of the plaques near the edges of the drive are bent, run over by indifferent and careless drivers. Well-manicured boxwoods and exotic trees dot the ground's rolling hills. In the very center of the cemetery atop a stainless steel flagpole the Star Spangled Banner flaps in a gentle breeze. Nearby, in section 16, is buried the man who killed Kathy Leissner Whitman -- her husband, Charles Joseph Whitman. On the right lies Margaret E. Whitman, his mother; he killed her, too.

Charlie's plaque is adorned by an engraving of St. Joseph, his patron saint. A rosary stretches across the top and around an opening where a vase should be; no one has adopted this grave. An engraving of the Virgin Mary and a rosary as well adorn Margaret's plaque. Yet another Whitman, John Michael, whom Charlie playfully called "Johnnie Mike," the victim of another tragedy, lies to the right. An angel with a spear adorns his plaque.

When Charlie and Margaret Whitman were buried together on 5 August 1966, the world was only beginning to comprehend the horror of what he had done, and yet his gray metal casket was draped with the flag of the United States, and, like his devoutly religious mother, accorded full burial rites of the Roman Catholic Church. The celebrant of the funeral Mass, Father Tom Anglim of Lake Worth's Sacred Heart Church, asked the world to try to understand; Charlie was obviously deranged.

We trust that God in his mercy does not hold him responsible for these last actions. We trust that our nation, with its traditions for fairness and justice, will not judge his actions with harshness.

But it was hard to understand. He had killed 13 others earlier in the same week, and four days later another of his victims, a critically injured 17-year-old girl named Karen Griffith, would die. She would not return to Austin's Lanier High School to join a senior class filled with the former students of Kathy Whitman's biology classes. Instead, Karen has her own weathered metal plaque in Crestview Memorial Park in Wichita Falls, Texas. What should have been her senior yearbook was dedicated to her and Kathy Whitman.

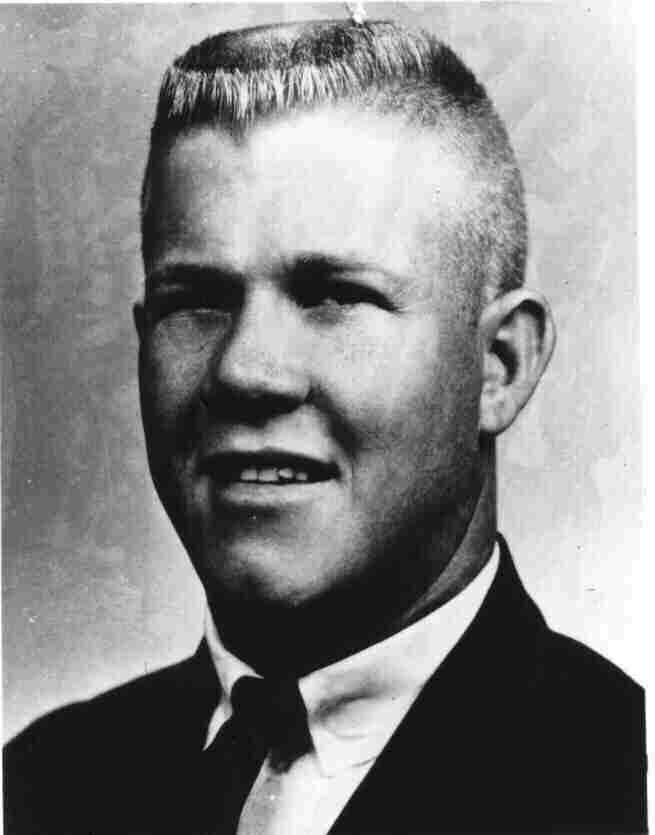

Surely,

Charlie Whitman had to have been an animal, void of virtue and conscience.

But the Austin American-Statesman described him as "... a good son,

top Boy Scout, an excellent Marine, an honor student, a hard worker, a

loving husband, a fine scout master, a handsome man, a wonderful friend

to all who knew him -- and an expert sniper." In articles that followed,

the Austin American-Statesman and the media in general presented a more

accurate and sober portrait, but no one would ever completely understand

Charlie Whitman.

Surely,

Charlie Whitman had to have been an animal, void of virtue and conscience.

But the Austin American-Statesman described him as "... a good son,

top Boy Scout, an excellent Marine, an honor student, a hard worker, a

loving husband, a fine scout master, a handsome man, a wonderful friend

to all who knew him -- and an expert sniper." In articles that followed,

the Austin American-Statesman and the media in general presented a more

accurate and sober portrait, but no one would ever completely understand

Charlie Whitman.

Probably very few people have ever visited both the Davis-Greenlawn Cemetery and the Hillcrest Memorial Park, but those who have can only be haunted by the similarities between the two places of peace. At Hillcrest visitors are seldom distracted by the traffic noise that comes from Interstate Highway 95, much like U.S. Highway 59 in Rosenberg. Here, too, weathered metal plaques lie on the ground everywhere. At Hillcrest industrial-sized sprinklers methodically shoot water over long distances. The twitching sounds blend with the noise of trucks using I-95. Workers nearby begin to prepare the resting place of another inhabitant, and the Davis-Greenlawn melancholy returns, and so do the pointless questions.

Twenty years after her death Kathy's father, Raymond W. Leissner, still referred to his son-in-law as "Charlie." Remarkably resigned to life without Kathy, Raymond Leissner harbored no ill will towards the man who murdered his only daughter. Instead, he believed that Charlie was driven to madness by a brain tumor discovered the day after his life ended as violently as that of his victims. "He was a brilliant boy," Leissner said. But Raymond Leissner could not understand either. "It's neither here nor there. It's done. It's over with; it's gone. There's no use trying to find out why...I got my consolement from Almighty God. I kind of left it in his hands. That's the only way to live a decent life."

It took Charles

Whitman an hour and a half to turn the symbol of a premier university into

a monument to madness and terror. With deadly efficiency he introduced

America to public mass murder, and in the process forever changed our notions

of safety in open spaces. Arguably, he introduced America to domestic terrorism,

but it was terrorism without a cause.

It took Charles

Whitman an hour and a half to turn the symbol of a premier university into

a monument to madness and terror. With deadly efficiency he introduced

America to public mass murder, and in the process forever changed our notions

of safety in open spaces. Arguably, he introduced America to domestic terrorism,

but it was terrorism without a cause.

In 1991 a University of Texas employee stated, "I can tell you now with total veracity that never once in the past 25 years have I looked at the Tower and not thought about Charles Whitman." Another UT alumnus, William J. Helmer, presently a contributing editor for a major magazine, lamented, "I can't quite shake an ever so slightly uneasy feeling that the Tower, somehow, is watching me." On the hundredth anniversary of the founding of Austin's Brackenridge Hospital, where so many lives were lost and saved because of Charles J. Whitman, one of the saved, Robert Heard, told the world of how he once suffered from recurring nightmares: "In my dreams, I'm looking through that scope at me, running. And I see the cross hairs right over my chest."

"He was our initiation into a terrible time," reflected a Guadalupe Street vendor. "... we grew numb. He was supposed to be an all-American boy. The sad thing is, maybe he really is."

In an article

in Esquire in August, 1977, noted author Harry Crews wrote of a visit to

the University of Texas and how his host gave an unsolicited tour of the

Tower massacre site. "That mindless slaughter was suddenly alive and

real for me, as though it were happening again, and it was all I could

do to keep from running for cover." Crews noticed his host glancing

over his shoulder as they walked across UT's South Mall. Later in the evening

Crews returned to the Tower and as he stared upwards, a disturbing personal

revelation occurred: "What I know is that all over the surface of

the earth where humankind exists men and women are resisting climbing the

Tower. All of us have a Tower to climb. Some are worse than others,

but to deny that you have your Tower to climb and that you must resist

it or succumb to the temptation to do it, to deny that is done at the peril

of your heart and mind." [Italics added]

In an article

in Esquire in August, 1977, noted author Harry Crews wrote of a visit to

the University of Texas and how his host gave an unsolicited tour of the

Tower massacre site. "That mindless slaughter was suddenly alive and

real for me, as though it were happening again, and it was all I could

do to keep from running for cover." Crews noticed his host glancing

over his shoulder as they walked across UT's South Mall. Later in the evening

Crews returned to the Tower and as he stared upwards, a disturbing personal

revelation occurred: "What I know is that all over the surface of

the earth where humankind exists men and women are resisting climbing the

Tower. All of us have a Tower to climb. Some are worse than others,

but to deny that you have your Tower to climb and that you must resist

it or succumb to the temptation to do it, to deny that is done at the peril

of your heart and mind." [Italics added]

In 1991, twenty-five years after the Charles Whitman murders, Catherine H. Cantieri summed up the danger in trivializing and forgetting details.

After 25 years and the attendant anniversary requiems, the story loses something. The edges blur, the facts lose meaning, the horror evaporates as it becomes just another media circus brought to you at 6 and 10 by concerned-looking anchors. The salient points, the meat of the story, are tossed aside, although they are the stuff that will make you lose sleep.

For individuals affected by the tragedy, like Raymond W. Leissner, there is wisdom in accepting what happened in Austin, Texas, on 1 August 1966 as something that can never be understood. Accepting the unknown as part of God's plan often brings peace and comfort to the faithful and the bereaved; it enables them to go on with their lives. But for society, and institutions, the crime looms too large to be forgotten, and periodic attempts to understand what happened and why are worthy; since 1 August 1966 there have been other Charles Whitmans, and there will certainly be more. Potential mass-murderers live among us; some of them are nice young men who climb their towers. It is no longer enough to look upon the University of Texas Tower and sigh, "This is where the bodies began to fall," because the story is larger than that. It is a story of how a nation discovered mass murder, and its vulnerability to the destructive power of a determined individual.

Gary M. Lavergne

Cedar Park, Texas

31 May 1996

| Gary's Bio |Before Brown| Worse Than Death| Bad Boy From Rosebud | Sniper in the Tower | Cajuns |